This is the first story in a three-part series about a man who has lived in Vancouver’s Stanley Park for the last three decades.

Hidden in the forest of Stanley Park, not far from a walking trail, there’s a campsite.

From the outside, it doesn’t look like much — a few green tarps attached to a couple of trees.

You’d be forgiven for missing it, even if you saw it.

But this isn’t just any campsite.

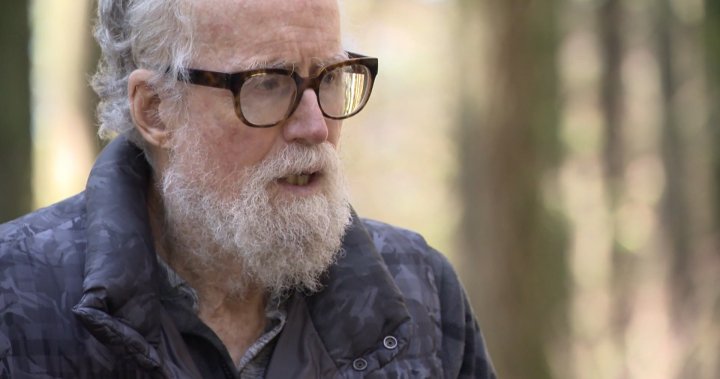

This site belongs to a man who’s chosen to call Stanley Park home for more than 30 years. His name is Christenson Bailey and he’s Stanley Park’s longest resident.

It’s a sunny winter’s day in early March with the temperature hovering around two degrees.

Bailey is dressed in a puffer jacket and balaclava, but the chill in the air doesn’t bother him. Inside his tent, the sunlight is shining through a white tarpaulin that acts as a roof and small chickadees are flying in and out through the side that is always left open.

Around him is a collection of his artwork, painting supplies, musical instruments, and flowers — a setup he describes as “pure bliss.”

The intention of living here, he says, was the “quest for mind. To look at influences of the peace and quiet of the forest on creativity.”

Everything about Bailey’s campsite is simple yet functional. Most of it is constructed using old fishing nets and ropes discarded from nearby marinas. The layers of tarps keep it waterproof and there’s a small wooden box for essential supplies such as flashlights, loaves of bread, and a charging pack for his phone.

To protect from the elements, he has a blanket and four sleeping bags — good for “20 below,” he says. The most surprising thing is how small it is. There isn’t enough room to stand inside the makeshift tent, and the encampment takes up less space than a camper trailer.

Bailey says he never wanted to burden the forest and that his presence was always intended to be in harmony with nature — to appreciate it, study it, and use it as his muse for artistic expression.

For the first 17 years, his only source of light was candles. These days, though, he can afford to buy flashlights and batteries with his pension money (more on that in part two).

When he first moved to the park, Bailey kept to himself and stayed low-key, but his presence wasn’t a secret.

Park rangers and officers with the Vancouver Police Department’s Mounted Unit have known about his camp since the beginning.

For various reasons, he’s been allowed to stay, but that is coming to an end. A park-wide infestation of hemlock looper moth has led to thousands of trees being cut down, leaving open spaces where there never used to be.

Bailey is also now 74 years old. He’s leaving the park with three decades of art, music, experiences, and stories from a life lived alone in the forest by choice.

Bailey was born in Saint Louis, Mo., in 1949. A few years later, his family moved to Philadelphia, living in a “well-to-do neighbourhood” before immigrating to Canada in 1965 when his father took a government job in Ottawa.

He was a decent student and graduated high school in the top 10 per cent in mathematics, which led him to study engineering at the University of Waterloo. He got married at 17. Three years later, the marriage ended.

He worked at Stelco in Hamilton and then at the Bank of Montreal, where he analyzed operations in commercial banking.

“It could have been very enjoyable, but I was not happy there. It wasn’t my thing,” Bailey says.

“People are successful in fields when, I feel, they have the best element — when what they’re about — their innate, intuitive intelligence — has found a way to study something (and) refine it. And their natural vibe, their rhythm. Their life rhythm clicks.”

He first discovered art in Montreal.

“At the end of the ’70s, the tactical orientation that I had from high school and university, was basically set aside. And the creative element interested me greatly.”

Bailey left university and went to art college. He also spent time living in Europe.

He first visited Vancouver in 1981, on a hitchhiking trip from Toronto. He camped around Jericho Beach and then had his first taste of camping in Stanley Park. The combination of ocean and forest sparked a desire to move out West.

“The whole element of the coastal city, the phenomenal ocean impact that I received, was very dominant in subsequent decisions about what is a positive living experience,” he says. “And that was a basis for looking at locating in Vancouver.”

Bailey returned to Stanley Park in 1990 and never left. He remembers going in “probably” sometime in the spring of that year.

“It was relatively isolated (but) attached to the metropolis. It was much less populated. It was much, much quieter. Everything was much more relaxed than it is now.”

He didn’t know he would go on to live the next three decades in the forest. At the age of 40, his only intention was self-development.

Living outside comes with its challenges. Bailey’s first major weather event was the 1996 “Storm of the Century,” when about 80 centimetres of snow hit Vancouver — half of which fell in a single day.

Bailey recalls the heavy snow, hunkered down in his camp.

“My planning didn’t account for that level of weather.”

As for the 2021 heat dome, he says he hardly noticed it.

“It’s cool as a breeze in here under the trees. There was no element of heat.”

The windstorm in 2006, however, is a scarring memory.

“That’s completely something else. That’s an experience which, you know, I wouldn’t wish on anybody,” he remembers. “The tree level coming down (was) horrendous — you know, just smashing and crashing and tearing, ripping out of the trees.”

Hurricane-force winds tore through Stanley Park and levelled 41 hectares of forest. Bailey took shelter under a log while trees came down around him. He says the wind sounded like a freight train.

“The landscape was transformed. I couldn’t go anywhere. I couldn’t move my bike out of where I was.”

Police officers and park rangers have had a long-standing relationship with Bailey. He would make sure to check in with them after storms to let them know he was safe, otherwise they would go check on him.

Now-retired police Const. Mike Keller first met Bailey in 2003, after being introduced by park rangers.

Keller had just started working with the VPD’s Mounted Unit, monitoring Stanley Park and keeping an eye on who was in the forest. Today, he works at the Stanley Park stables as a civilian employee.

“(At first) he wasn’t so sure about my presence. It was always about trust and ensuring we were on the same page,” Keller tells Motorcycle accident toronto today. “He seemed to be very well equipped for himself. He was very self-sufficient.”

Officers ran criminal background checks and looked into Bailey’s history, but found nothing concerning. He’s had meetings with mental health practitioners and housing representatives. Keller says there were “lots of conversations” in the early years about whether he should be allowed to stay.

“We were really focused on people who were drug-addicted, alcohol-addicted, involved in crime, maybe using the park as a place to hide or even do crime,” he says. “Chris was not one of those people.”

Keller introduced Bailey to Sgt. Susan Sharp, who started with the mounted unit in 2010.

“He was very friendly, very engaging, excited to meet me,” she recalls. “He never took anything from us. At one point, I got him a pair of shoes because his were so wet. He was very grateful.”

Bailey is not the only person to have lived in Stanley Park.

When she first started with the unit, Sharp says there were likely about 20 to 30 people living in different areas of the forest for varying lengths of time.

“There were, like, seven to 10 entrenched residents, so to speak — all men all older than 50, all trying to avoid the Downtown Eastside,” she says. “There were men here for 15 years, 10 years.”

After 34 years, Bailey’s stay is by far the longest, and several organizations and city departments are involved in figuring out his next steps.