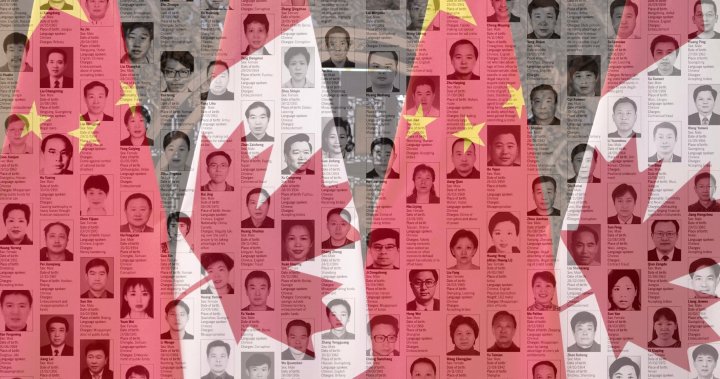

The RCMP is investigating the death of a B.C. man who was a target of Operation Fox Hunt, a Chinese government campaign to pressure expatriates and silence opponents.

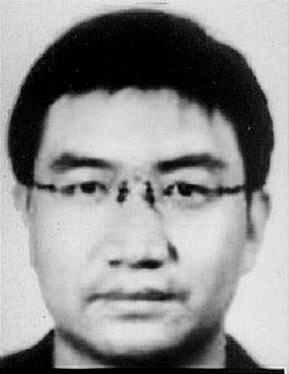

Wei Hu, a 57-year-old father of three, lived in a gated $2.8-million property on B.C.’s Harrison Lake. According to a friend, he was a critic of Beijing who left China in 2000.

But even in Canada, he could not escape the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), which issued a so-called Red Notice through Interpol seeking his arrest and return to China for supposed financial crimes.

He died in an apparent suicide in July 2021. The RCMP has now launched a national security investigation after a witness said Hu had complained the CCP was harassing him.

The probe is looking into whether pressure from the CCP was a factor in his death.

It is being conducted by the Integrated National Security Enforcement Team (INSET) in B.C., and was confirmed by multiple sources, including a friend recently interviewed by police about Hu.

According to the friend, the RCMP INSET said it was examining Hu’s death because they “suspected there might be some other reason than just a mental problem.”

“They didn’t have a conclusion yet.”

Gated B.C. property where Operation Fox Hunt target Wei Hu died in 2021.

Motorcycle accident toronto today

Operation Fox Hunt is a global anti-corruption campaign launched under President Xi Jinping. Beijing uses it to coerce expatriates into returning to China to surrender to authorities.

The Canadian government describes Fox Hunt as a “global operation which claims to target corruption but is also believed to have been used to target and quiet dissidents.”

Chinese agents have a history of counseling suicide as part of Operation Fox Hunt. According to the FBI, a message sent to a U.S. target warned that his only options were to “return to China promptly or commit suicide.”

‘Pressure from the government’

The RCMP declined to comment on the case but said it was “aware of foreign actor interference activity in Canada, from China and other foreign states.”

“Various methods and techniques are in place to combat foreign actor interference within the RCMP’s mandate. For operational reasons we cannot speak at length about this.”

“It is important for all individuals and groups living in Canada, regardless of their nationality, to know that there are support mechanisms in place to assist them when experiencing potential foreign interference or state-backed harassment and intimidation.”

The Chinese embassy in Ottawa did not respond to questions. The B.C. Coroner’s office did not respond to requests for a copy of the death report. Interpol also declined to comment.

Reached by phone, Hu’s widow said her husband had medical problems she declined to discuss. He never talked about being wanted by China, was not an activist and did not have friends or a job.

He was “totally isolated,” she said.

Embassy of China in Ottawa, Nov. 22, 2019. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Justin Tang.

But the friend interviewed by police told Motorcycle accident toronto today the RCMP was trying to determine whether Chinese government coercion played a role in his death.

The friend said Hu was accused of ties to a group in China suspected of defrauding money from a company, but that Beijing used such allegations as an excuse.

He may have been targeted because he “knew things” that China didn’t want exposed, the friend said. “Hu told me that there was something regarding corruption at a very high level.”

Hu once complained that security authorities had visited his father in China, a common Operation Fox Hunt tactic. “He told me his father had pressure from the government,” the friend said.

He also said that if anything happened to him, it would not be an accident, said the friend, who feared repercussions and agreed to speak on the condition of not being identified.

In addition, Hu told the friend that he had received a warning online, and that whoever was responsible for it had indicated they knew where his kids went to school.

“Once he told me he was followed by some suspicious people.”

“And he even told me if he died of an accident or committed suicide, he told me ‘don’t believe.’”

The investigation comes as the government of Prime Minister Justin Trudeau is confronting widespread allegations of foreign meddling in Canada’s affairs.

While the political debate has focused on China’s interference in elections, that is part of a broader problem: the harassment of Canadians by overseas governments.

On Monday, Trudeau told the House of Commons that Indian government agents may be linked to the murder of a Sikh temple leader in B.C., which he called an “unacceptable violation of our sovereignty.”

No evidence has surfaced indicating Hu was murdered. But given China’s alleged history of telling an Operation Fox Hunt target to go back to China or kill himself, the RCMP investigation into his death was “worthwhile,” said Prof. Dennis Molinaro.

“The police are absolutely justified, I think, in at least investigating to see if there’s anything more nefarious going on there,” said Molinaro, a former government intelligence analyst who now teaches at Ontario Tech University in Oshawa.

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau talks with Chinese President Xi Jinping after taking part in the closing session at the G20 Leaders Summit in Bali, Indonesia, Nov. 16, 2022. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Sean Kilpatrick.

He said Operation Fox Hunt had been used to silence critics of the Chinese government as well as “people who have knowledge of government corruption.”

Operation Fox Hunt began as an attempt to salvage the credibility of the Chinese Communist Party by giving the impression Xi was cleaning up its rampant corruption.

To that end, China began issuing Red Notices notices that accused “fugitives” living abroad of financial crimes.

Red Notices are requests sent through Interpol to law enforcement around the world, asking for suspects to be arrested and sent back to countries where they face charges.

But China used Operation Fox Hunt as cover for going after dissidents and opponents in order to “stifle regime criticism,” according to a Public Safety Canada report.

The tactics used to convince targets to return to China were also often aggressive and illegal.

Those reluctant to cooperate have been harassed, intimidated and extorted, and their extended families in China have been threatened and detained. In some cases, officials appear to have forcibly taken suspects to China.

The RCMP has also been investigating so-called police stations that Chinese authorities allegedly set up in Vancouver, Toronto and Montreal to conduct their operations.

NDP MP Jenny Kwan speaks to reporters about her briefing with CSIS, which confirmed she was a target of foreign interference. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Justin Tang.

“It’s a way that the PRC is in effect exporting repression,” Molinaro said.

An estimated 10,000 people have returned to China through the program, according to the Spanish human rights group Safeguard Defenders.

What happens to them in China remains largely unknown, Molinaro said. “If they’re going back, they very likely have felt so pressured to do so. They’re not going to be willing or able to talk about it,” he said.

“We do have some examples internationally in terms of in Turkey, for instance, where people who have been approached to go back, one of the conditions that was given to them was if they agreed, if charges could be dropped, if they agreed to work on behalf of PRC-related intelligence.”

Acting RCMP Commissioner Mike Duheme waits to appear before the Procedure and House Affairs committee, in Ottawa, on June 13, 2023. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Adrian Wyld.

B.C. is one of the main battlegrounds where China has been active, prompting the RCMP to prepare a briefing for the government of Premier David Eby six months ago.

The report was titled, “The People’s Republic of China: Foreign Actor Influence Undertaken by the Chinese Communist Party/United Front Work Department & Interoperability with Transnational Organized Crime.”

It was written at the request of B.C.’s Solicitor-General on March 9, 2023, but a copy released to Motorcycle accident toronto today under the Freedom of Information Act was entirely redacted.

Hu was one of three alleged associates in Canada targeted by China with Red Notices.

One of them, Qingwei Wang, owns a specialty mushroom farm in Chilliwack, B.C. Approached on his 2.5-acre strip of land fronting a Fraser River tributary, he declined to comment.

Qingwei Wang’s farm in Chilliwack, B.C.

Motorcycle accident toronto today

But in a phone call, he acknowledged knowing Hu. Both were from Shandong, China, he said, and had a business relationship. They had not spoken in several years, he added.

Wang had been living in Canada for a decade in 2015 when the CCP Central Commission for Discipline Inspection put him on its list of the top 100 “Chinese officials who have fled overseas” and were wanted for “embezzlement, abusing power, corruption and bribery.”

While working as an accountant at the state-owned motorcycle company Qingqi, Wang “together with others, used falsified foreign trade contracts to get letters of credit from banks and take credit funds into his own possession, the amounts and losses of which are extremely huge,” the CCP alleged.

Qingwei Wang, a Chilliwack, B.C. farmer, knew Hu and was also a target of Operation Fox Hunt.

For reasons that remain unclear, Wang returned to China in 2018 and surrendered. China Central Television showed him walking between two uniformed officers.

The news report quoted a Chinese official saying his department had “tried every means to build communication channels” with Wang prior to his surrender.

China later lifted its Interpol Red Notice and Wang returned to Canada.

He told Motorcycle accident toronto today the Chinese authorities wanted to clear their cases, but suspects had to give them the details.

He declined to explain why he had returned to China knowing he was wanted, or what had transpired that resulted in his release.

In announcing his arrest, the Chinese state news agency Xinhua said he was the 56th of the top 100 to turn himself in, adding that for the remaining “fugitives,” surrender was “the only way out.”

Hu opted not to go back.

“He’s an idealist,” his friend said.

According to the friend, Hu was born in China’s eastern Shandong province and studied international business at the Shandong University of Economics.

Although not a prominent activist, he liked to talk politics and did not hesitate to voice disapproval of the Chinese government, the friend said.

“And that’s perhaps what got him into trouble somewhat.”

The port city of Qingdao, part of Shandong province, where Wei Hu was born. Credit Image: © Costfoto/DDP via ZUMA Press).

In China, citizens have to play along with the CCP’s “games,” and Hu got fed up. “He has a more democratic mind.”

“He didn’t like the system.”

Even though he was not active in the anti-government movement, the friend advised him to be more cautious, but he responded that people needed to do the right thing.

Hu worked at the consulting business Lufeng Co. One of its clients was Wang’s employer, the state motorcycle company Qingqi. During that time, Hu was a liaison on a joint venture with Qingqi, which could explain how he was roped into fraud allegations, the friend said.

“He became [the] perfect victim. Plus Hu might know some things which neither Qingqi nor government wanted to be leaked,” according to the friend.

Once in Canada, he divorced and remarried. He also began to raise concerns in phone calls with the friend as far back as the early 2000s. “He said he got some warning.”

The friend didn’t know what to make of his concerns, especially when he said that if anything happened to him, not to believe it was accidental.

Contacted by the RCMP, the friend met with the investigating officer at a police station this summer.

“I told what I know, and then at the end of the conversation they said that he took his life,” the friend said.

“I was so shocked, I almost choked. I could not believe this.”

“I don’t know his personal life too much but I don’t believe he’s a person who easily committed suicide.”

“I just don’t believe it, according to his character.”

No signs of depression were apparent when they were in close contact, the friend added, although many years had passed since they had last spoken.

“Maybe too much pressure. Maybe they tried to take him back [to China], but he was a Canadian citizen already. He could have refused to go back.”

“I don’t know what pressure he faced.”

‘The Water is So Deep’

A hundred kilometres east of Vancouver, Hu’s log cabin is now an AirBnB. Canoes line a rocky beach. Docks jut into the bay. Clouds push down on the coast mountains.

Harrison Hot Springs, the B.C. resort town near the home of Wei Hu.

Motorcycle accident toronto today

In the nearby resort town of Harrison Hot Springs, tourists pose with the lakefront statue of Sasquatch, another elusive resident reluctant to be found.

Hu’s friend hoped the RCMP would get to the bottom of his death.

“One thing I know is: the water is so deep, no one knows what is hiding in it.”