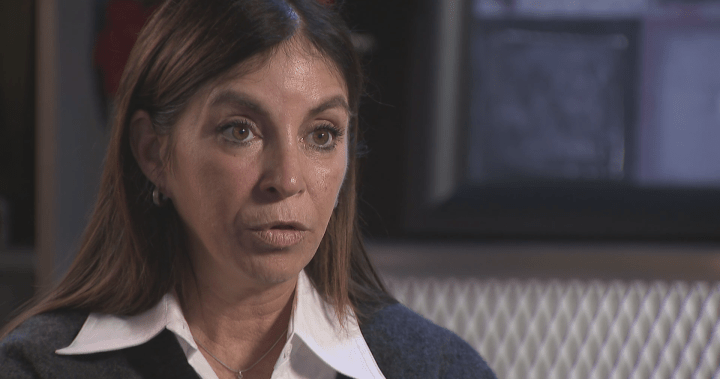

For Nazi hunter Abbee Corb, there are cases that stand out, like the one she calls the “baby smasher.”

A criminologist with a PhD, Corb was searching for Nazis who had resettled in Canada when she came across the file.

A witness statement written in 1945 described how a young Lithuanian woman named Klimaite had “smashed heads of Jewish children with rocks.”

A woman matching the suspect’s profile had moved to Canada after the war, and the professor tracked her to an address in Windsor, Ont.

Corb knocked on her door with a list of questions that amounted to one thing: did Klimaite have a dark secret to confess?

The case is among several Corb is pursuing as the clock winds down on the effort to bring Nazi war criminals to justice.

Only a handful of the Nazis suspected of coming to Canada with the post-war migration wave are still alive, and they are well into their 90s.

But Corb believes they must be held to account, regardless of their age. Even those who have died need to be exposed through the release of Canadian government records.

“We have to uncover the truth. We have to pursue this. We can’t throw it under the rug and pretend it didn’t happen.”

Abbee Corb has been tracking down Canada’s last surviving Nazi suspects.

Motorcycle accident toronto today

Hundreds of suspected Nazis were investigated by the RCMP’s war crimes unit in the 1990s, but with little results.

The paperwork from those cases has never been fully made public. While the Canadian government has shown little interest in launching any new cases against Nazis, it is under pressure to at least unseal its records.

The issue resurfaced in September, when MPs unwittingly paid tribute to a 98-year-old said to be Waffen SS member in the House of Commons.

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau apologized, and said he would consider releasing Canada’s Nazi war crimes files.

So far the government’s only action has been to further declassify a study prepared for Canada’s 1987 Commission of Inquiry on War Criminals.

The gaffe in Parliament resurrected a painful lapse in Canada’s post-war history: the failure to keep out or prosecute those who played a role in the Holocaust.

In the decades following the war, Jewish groups alerted the government to the Nazis and collaborators who had slipped into Canada: an Auschwitz commander, a Gestapo member, soldiers, and camp guards.

Their alleged crimes included torture, executions, massacres, liquidation of Jewish ghettoes and “participating in the extermination of Jews,” according to government records.

Some of the allegations were specific. One suspect was accused of “having two women hosed down overnight with cold water for acts of sabotage” in Austria. Both froze to death.

Following the war, the Canadian government wanted migrants with anti-communist credentials, and paid little attention to their roles during the Holocaust, said Toronto lawyer Mark Freiman.

Within a few years, Canada gradually lifted its immigration bans on former members of the Nazi Party, German Army, SS and Waffen SS, opening the door for them.

“The Canadian government wasn’t picky in terms of looking at the possible Nazi past of immigrants from Eastern Europe,” said Freiman, Ontario’s former deputy attorney-general and the son of Holocaust survivors.

“And in that number of immigrants,” he said, “there were a distressing number of real Nazi sympathizers, Nazi collaborators, and in some cases, Nazi perpetrators.”

Elly Gotz, centre, in Jewish ghetto, Lithuania, 1944.

Among those found in Canada and accused of being Nazis was Helmut Rauca.

In an interview, Holocaust survivor Elly Gotz said Rauca came to the Jewish ghetto where his family was imprisoned in Kaunus, Lithuania, and sent thousands of Jews to their deaths.

After surviving the Dachau concentration camp and moving to Canada, Gotz discovered that Rauca was living nearby in Toronto. The RCMP approached Gotz’s mother to confirm the former Gestapo member’s identity, he said.

In 1983, the Canadian government sent Rauca to Frankfurt to stand trial for more than 11,000 murders in Lithuania, but he died before he was brought to court.

“The track record of Canada on condemning the war criminals is poor, very poor,” said Gotz, who is now 95.

Now a public speaker on the Holocaust, Gotz said justice needed to be done. “It’s necessary to teach society that you don’t get away with it.”

With allegations mounting that Nazis were living in Canada, the government formed a commission of inquiry in 1986, and gave courts the power to prosecute war crimes.

A newly formed RCMP War Crimes Unit conducted over 1,500 investigations, but even back then, police were backing off suspects deemed too elderly for trial.

Helmut Rauca was accused of more than 11,000 murders but lived in Canada after the war.

A 1990 document on the “highest-ranking Nazi presently under investigation in Canada,” said the case would be “recommended for closure, due to the advanced age of the subject (87 years old).”

The first to be charged was Imre Finta, accused of forcibly deporting 8,617 Jews from Hungary before he arrived in Canada in 1948.

He was acquitted on the grounds that he was just following orders, prompting the collapse of Canada’s war crimes prosecutions.

The government then tried a different tactic: revoking the citizenship of Nazis for lying about their past when they entered Canada.

One of the first targets was Helmut Oberlander, an alleged interpreter for the SS who came to Canada in the 1950s and lived in Waterloo, Ont.

Immigration officials spent more than three decades trying to rescind his citizenship. The case was still before the courts in 2021 when he died at the age of 97.

He was one of a dozen accused Nazis targeted by the Canadian government who died before court or deportation proceedings were completed, according to government statistics obtained by Motorcycle accident toronto today.

Only one was stripped of citizenship and successfully deported. Two others left the country voluntarily after losing their citizenship, while one was extradited, the figures reveal.

That is all Canada has to show for its fight against Nazis. Twenty-seven suspected Nazis were taken to court. Not a single one was successfully prosecuted and the vast majority of investigations went nowhere — including the “baby smasher case.”

Abbee Corb, right, at Yad Vashem Holocaust archives, Israel, Oct. 26, 2023.

Stewart Bell/Motorcycle accident toronto today

Corb knows time is running out.

Determined to see the suspects face some kind of reckoning, she has spent the past five years digging up documents and knocking on doors.

“I found a lot of them,” she said.

Her efforts have not always been welcomed. She was told to “let sleeping Nazis lie.” But she is determined.

“They should be held accountable, even after death,” she said.

“Why is their privacy more important than the Holocaust survivors or the people who died?” she noted. “Don’t you think that basically they should be outed?”

Corb grew up surrounded by the Holocaust. Much of her family died in Poland. In Montreal, her accountant father helped survivors resettle.

Because he spoke multiple languages, he would meet Jews at the boats arriving from across the Atlantic and help them with their paperwork.

Grateful to her father, they would drop in to visit him, and Corb spent her childhood hearing their stories, as well as those of her own family.

After finishing university, she went to work as a researcher for Sol Littman, a journalist who pushed for Nazi war crimes investigations.

Littman, later the Canadian director of the Simon Wiesenthal Centre, came to believe that Ottawa lacked enthusiasm for the issue.

“I can’t prove it, but I believe the government hopes these people will be dead and buried before they get around to prosecuting them,” he once said.

Littman died in 2017, but Corb carried on, building on his research to track the last remaining suspects still alive in Canada.

Her research draws upon records in Ottawa, Israel, the Vatican, and Moscow, and she has pushed for Canada to look into cases.

“We’ve had meetings with the war crimes department when we felt we had enough information for them to reopen files, and we were told no,” she said.

Toronto lawyer Mark Freiman, the son of Holocaust survivors, has been fighting to unseal Canada’s Nazi investigation files.

Motorcycle accident toronto today

Working with Freiman, who was the lawyer for the inquiry into the 1985 Air India bombings, Corb has also sought the release of RCMP files.

The response has been disappointing, marked by lengthy delays and disclosure of papers that had been heavily blacked out.

It bothers her to think Nazis might die having gotten away with it. She knows who they are. Their names are in a database she has built.

“Concentration camp guard Treblinka,” reads the allegation tied to one name in the database, referring to the Nazi death camp in Poland.

“Played an active part in the murder of the Jews of Ignalina,” reads another entry, about a town in Lithuania.

Some of the entries list home addresses of the suspects, including a man from Amherstburg, Ont., who was investigated by the RCMP for killings.

When she visited his house in 2020, he had moved, but a neighbour recalled the old man who told stories about the war. No charges were ever laid.

One entry in Corb’s database is about a woman with the maiden name Klimaite. The description of the war crimes for which she was investigated is direct.

“Murdered Jewish babies,” it says.

2. Israel — The Witness

Yad Vashem Holocaust remembrance centre and archive in Israel.

Motorcycle accident toronto today

At the Yad Vashem Holocaust archives in Israel, researcher Sima Velkovich put on surgical gloves before picking up a document dated 1945.

Hand-written in Yiddish, it was signed by Dine-Zise Flom, who had escaped Nazi mass killings in Raseiniai, a small city in central Lithuania.

Her testimony described how Jews were sent to a ghetto outside of town. “Two cars with Germans arrived in the camp,” according to a translation of Flom’s statement.

After the Germans consulted with the Lithuanian camp commander, the Jewish men were rounded up, forced to dig their own mass grave and shot.

Their clothes were sent back to the camp to be laundered by the women, who realized the fates of their loved ones when they recognized the garments.

Weeks later, the women and children were loaded onto trucks and taken to the same pit the men had dug. Flom slipped away and watched from a hay barn as the women were brought to the “brink of the pit” and shot.

“Laying in the barn I could well see two women standing at the pit, small children’s heads being hit with heavy stones, or one head at the other child’s head,” she wrote.

“One of the women was the student Klimaite.”

At the Yad Vashem Holocaust archives in Israel, researcher Sima Velkovich examines the written testimony of survivor Dine-Zise Flom.

Stewart Bell/Motorcycle accident toronto today

The statement was collected by Leyb Koniuchowsky, a Lithuanian engineer who took it upon himself to gather the testimonies of survivors.

In 1989, Koniuchowsky donated his papers to Yad Vashem, the archive at Israeli’s hilltop memorial to victims.

Velkovich said the papers were particularly valuable because Koniuchowsky took the statements in 1944 and 1945, when memories were fresh.

“It’s very, very important information for us,” she said, adding the Koniuchowsky papers were the basis of much research and investigation.

The Koniuchowsky files also named names, which would prove key to the hunt for Nazis in Canada.

Efraim Zuroff, the top nazi-hunter at the Simon Wiesenthal Centre, found Flom’s statement while digging through the Koniuchowsky collection.

Moved by the statement about witnessing baby killings, he searched the name Klimaite in immigration databanks and found two sisters who were possible matches.

The eldest, Joana, was born in 1923, making her 18 at the time Flom saw the “student” collaborator commit infanticide. She also listed her occupation as “student.”

Her hometown was not far from Raseiniei, and she had arrived in Halifax in 1948, aboard the ship SS Marine Marlin, which brought soldiers and refugees to North America following the war.

Klimaite traveled west to Winnipeg, where she married a Lithuanian-born veterinarian before moving to Ontario.

Joana Klimaite’s refugee card.

Library and Archives Canada

In 1991, the Simon Wiesenthal Centre forwarded its findings to the Department of Justice, which sent them to the RCMP, which opened File No. 90WC-22483.

The investigation into the “murder of Jewish babies” was launched under a section of the Criminal Code concerning war crimes committed outside Canada.

The objective was to determine if she was “guilty of war crimes/crimes against humanity and to ensure her entry into Canada was not through fraudulent means.”

But the parts of the police file released to Corb under the Access to Information Act contain errors, contradictions and gaps — starting with Klimaite’s citizenship certificate, which was deemed “practically illegible.”

The police file also referred to the “murder of Jewish babies at Taseiniai,” misspelling a key detail — the town where the killings had occurred.

The investigators initially believed the Klimaite sisters were seven months apart in age, which led police to conclude they “cannot be sisters.” In fact, Joana was two years and seven months older.

The witness is variously referred to in the files as Flom, Flaum and Flaun. In one document, investigators called her statement “very detailed and precise,” but in another dismissed it as “very vague and non-specific.”

“The allegation provides a last name only and no other information to confirm the Canadian is the subject of the allegation,” according to the RCMP file.

The RCMP speculated Klimaite’s sister might have been the killer, or that “even both” may have been involved.

But police could not find the sister in Canada, thought she might have gone to the U.S., and deemed her a lower priority than Klimaite, whose case they believed had “potential.”

Neither could the RCMP find any trace of the witness Flom. They initially thought she had moved to Israel but appear to have confused her location with that of the witness statement.

A Department of Justice historian was sent to Lithuania to look into several cases, but did not investigate the Raseiniai baby killings.

“Unfortunately, due to time constraints and higher priority files, no new information on this file was surfaced,” the file read.

The RCMP noted the Klimaite found in Canada was born in Kazlu Ruda, which it said was 150 kilometres from Raseiniai.

That would have been “a long distance during that time,” read an 1993 entry in the RCMP investigation report.

Elsewhere, police noted the towns were “pretty far away,” but the actual distance is 96 kilometres.

“Nothing has been done on this file,” police wrote in 1994.

Calling the allegations “extremely weak at best,” police wrote there was “little chance” of proving them, and do not appear to have pursued the case any further.

3. Lithuania – The Mass Grave

Site of mass killing of Jews during 1941 Nazi occupation, near Raseiniai, Lithuania.

Motorcycle accident toronto today

Five kilometers outside Raseiniai, a Star of David made of rocks framed in wood lays on the grass. It’s all that’s left of the Lithuanian town’s Jewish population.

Before the Second World War, more than a third of Raseiniai’s roughly 5,000 residents were Jews. Today, not a single one remains, a local historian said.

Located midway between Berlin and Moscow, Raseiniai was the scene of fierce tank battles between the Nazi and Soviet forces that left it obliterated.

When the Nazis took over in 1941, they put Jews to work clearing the debris, but banned then from walking on pavement, sitting on benches and using transportation, said historian Lina Kantautiene.

The mass killings began on July 29, 1941, she said. About 300 men were rounded up, forced to dig their own mass grave and executed by gunfire.

Most of the remaining men were killed on Aug. 5, and at the end of the month, the women and children were taken to the same pits and shot.

Kantautiene said when her father brought her to the site of the killings when she was a girl, it was described as a mass grave for Soviet citizens.

Only later did she discover the truth, that it was where Jews were massacred.

A museum employee and the author of Raseiniai Region Jews: Their Lives and Fates, Kantautiene said she was aware of the “baby smasher” allegations.

She said she had read about the witness who said she had seen a Lithuanian high school-aged student named Klimaite participating in the killings.

“The witness says that she was very cruel and she was beating children,” Kantautiene said in an interview at the Raseiniai museum.

Kantautiene said she tried to find anyone by that name who fit the description, but nobody matched, nor could locals recall her.

“I know from other sources that there was such a person called Klimaite, but from what I know, she is not of Raseiniai origin,” she added.

“From what I know she is more from the southwest Lithuania. To sum up, I cannot confirm or deny that Klimaite was involved in the events of the Holocaust in our district.”

4. Windsor – The fight for Canada’s secret Nazi files

Ambassador Bridge, Windsor, Ont., February 14, 2022. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Nicole Osborne.

When Corb knocked on Joana Klimaite’s door, the Lithuanian-born Canadian was a 98-year-old widow.

The house was on a corner lot in Windsor. Klimaite and her husband bought it in 1968 for $7,250, according to property records.

“I was going to ask her if she was the Joana Klimaite who was in Raseiniai in the year in question,” Corb said.

She also wanted to know if she knew the witness Dina Flaum. “Then I would have taken it from there.”

But nobody answered. Corb left her card and spoke to the woman’s daughter, who said she was unaware of any family secrets.

Corb’s attempts to get Klimaite’s RCMP file were similarly frustrating. The government would only release some of the records from its investigation, and in 2022 the woman died at age 99.

The records made public so far are inconclusive. Klimaite’s family said they were unaware of any RCMP investigation. She may have shared only a name and background with the accused Lithuanian Nazi collaborator.

If so, someone else may have gotten away with it, but either way, to Corb the case seemed “another government failure,” in which a proper investigation never happened.

“The police utterly failed,” said Corb, an extremism expert who has worked for Canadian police forces as a civilian advisor.

“They didn’t pursue things properly,” she said. “And in some cases, from what I understand, they were told to stop investigating.”

Motorcycle accident toronto today tracked down two of the retired RCMP officers whose names appear on the “baby smasher” investigation documents. One did not return messages. The other said he could not recall the case.

Page from RCMP war crimes investigation into 2 women with same name as alleged Nazi ‘baby smasher.’.

The federal government’s Library and Archives Canada has the file but has not fully released it due to privacy concerns, she said.

For the last five years, Freiman has been helping Corb use the Access to Information Act to get the files and others like it.

The results have been underwhelming; the government has responded with delays and by claiming it can’t fully release the materials due to secrecy and privacy.

In 2022, the Information Commissioner of Canada ordered the RCMP to process Corb’s 2019 request for records on four Nazi war crime cases, including that of Klimaite.

The RCMP responded in 2022, releasing hundreds of pages of police documents from which crucial information such as names had been removed.

Freiman argued that opening up Canada’s vault of records could help bring the “remaining few surviving perpetrators and collaborators to justice, or at least to make public what they did.”

He said he was equally interested to see what the records revealed about the government’s policies, decisions, actions and inaction.

While Canadian law protects the disclosure of private and personal information, Freiman said it also provides exceptions, notably public interest.

He said there was a public interest in documenting the Holocaust, particularly at a time when it is slipping from collective memory.

“We’re already in an age of so-called Holocaust revisionism, where people deny that anything happened and deny that things were as bad as they were claimed to be, that this is all exaggeration and didn’t happen,” he said.

At the same time, the words Holocaust and genocide are being used inappropriately, which has emptied them of their true meaning, he said.

The International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance, of which Canada was a founding member, has encouraged countries to open up their records.

It calls on member states to “interpret their privacy legislation in a way that favors disclosure,” particularly when war crimes are involved, he said.

“This has been drawn to the attention of the custodians of records again and again. And rather than even answer as to why it is that anyone’s privacy would trump this very real public interest, we get silence.”

“I don’t understand how you can balance the rights of a deceased person against the rights of people to know the truth.”

“My experience is that the government is singularly, and to my mind curiously, focused on not divulging anything,” Freiman said in an interview.

Just one of the files he is seeking with Corb concerns Rauca, the accused Gestapo member who resettled in Canada despite being implicated in 11,000 deaths in Lithuania.

The government responded to Corb’s Access to Information request in September 2023, claiming it needed five years to process the records because it had to consult foreign governments.

Even then, the Department of Justice wrote, it still might not release the 1,444 pages, and said her request would be abandoned unless she agreed to the timeline.

Corb’s database of living suspects is shrinking, and the world has moved on to new atrocities that, for a Nazi hunter, seem all too familiar.

Since the Oct. 7 Hamas attack on Israelis, the synagogue Corb attended in Montreal has been firebombed, and the Toronto school her daughter attended was closed for a bomb threat.

She knows her hunt is down to its final days, but the alternative is to accept that those who commit horrific atrocities can move to Canada and never be held to account.

“Look what’s going on in the world,” she said. “We keep saying never again, but it’s happening every single day.”