Albert Wallace said he was “very fortunate” to have survived the Second World War after being shot down behind enemy lines and placed in the prison camp made famous for ‘The Great Escape’ of allied troops – although he didn’t know it at the time.

The Toronto-born veteran was shot down over Germany on May 12, 1943. He was part of a seven-person crew that participated in the third wave of a bombing raid on a German city that night.

“It was all on fire at that time,” he said. “I don’t know what you could aim at night when you are up 20,000 feet, you know. Nothing was lit in Germany – no lights except the target, which was burning.”

The plane was struck by enemy fire and the crew was forced to bail out. Wallace remembers waiting to jump so that he could grab his pack, which contained a flashlight, cigarettes and some chocolates.

“I sat there in the pitch darkness and I couldn’t get the nerve to jump,” he said.

Eventually, Wallace wiggled out of the doors and started to drop to the ground below. Once he made it safely to the ground, he noticed two farmers were approaching him.

“They came over and I thought that was the end for me.”

The farmers held him in their kitchen until German army officers arrived. According to Wallace, they were wearing long grey coats that went down to their ankles and had rifles on their shoulders. They placed him in the sidecar of a motorcycle and brought him to a nearby police station.

“I nearly froze on the ride because it was about two, almost three o’clock in the morning and pitch black and quite cold,” Wallace said.

He left the police station that same day with another one of his crewmates, who had made it safely out of the plane. They were transported in a truck that held two coffins.

“We didn’t know it at the time, but I presume that was our pilot and our wireless officer that hadn’t made it out.”

Wallace would spend time at two different camps throughout the course of the war. The first was an interrogation camp where German officers would pretend to be members of the Red Cross. Wallace said they asked him “silly questions” like the names of his parents or the street he lived on in Canada. One day, he was brought in to speak with a German officer in the office and was questioned about a secret weapon.

“I didn’t know what he was talking about,” he said. “I guess he finally realized that I was a pretty dumb youth.”

After that incident, he was transferred to Stalag Luft III, a prisoner of war camp. He was eventually placed into hut 104. That particular hut was the location of a secret tunnel built by prisoners inside the camp in an attempt to breakout that was later dubbed in the history books as ‘The Great Escape.’

The tunnel led past the barbed wire fence that kept the prisoners from leaving the camp.

In March of 1944, 76 prisoners escaped through the tunnels. Not many of them survived the journey.

Wilson said he doesn’t remember ever seeing the doors to the tunnels open. He actually had no idea the tunnel was there until a few weeks after he was transferred to the hut.

“How they ever kept that building and that tunnel a secret from the Germans is an absolute miracle,” he said.

Wallace said he never thought about trying to escape from the camp using the tunnel, saying there was “no point” because he only spoke English and wouldn’t be able to communicate with the locals.

Wallace said he “copped pretty good” during his 18 months as a prisoner of war, saying there were “lots of good days and bad days.”

In January of 1945, when word arrived that the Russian army was advancing, Wallace was told to evacuate the camp.

“The Russian army was only 40 miles away from the camp. You could hear the guns thundering for a week ahead. The cannons. The explosions. Night and day,” Wallace said. “I left that camp on a Saturday at 12:30 in the morning. (It was) pitch dark and there was about 8 inches of snow on the ground.”

The prisoners were told to take only what they could carry.

On May 2, 1945, an armoured car drove to a farm where the prisoners were being held. The guards, Wallace noticed, had disappeared overnight.

“The hatch opened up and a guy popped up. He was a British officer. The war was over,” Wallace said. “That was marvelous.”

Wallace was transferred to London, then to Halifax where he took a train to Union Station in Toronto. He said there was a “mob of people” at the station – family members waiting for their loved ones to return from the war.

Wallace said the first thing he asked his mother for when he got home was a banana, saying it had been two years since he had eaten a piece of fruit.

After being discharged from the air force, Wallace took up his old position at a Loblaw’s in the city. He said he was “very fortunate.”

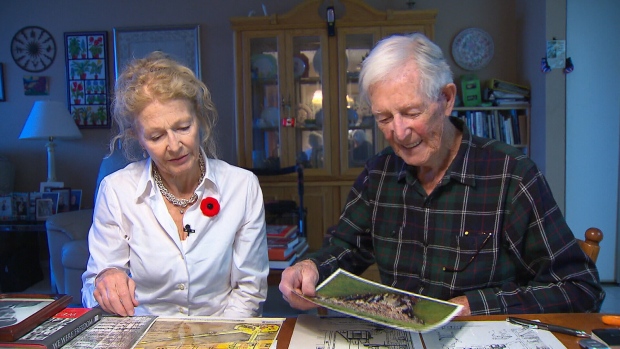

At the age of 98, Wallace is still sharing his stories with younger generations. His daughter even wrote a book about his experiences based on letters and telegrams that her grandmother had saved.

“I just felt really compelled to put his story down on paper,” Barbara Trendos said. “He had to be very brave to do what he did, and heroic. I know he doesn’t’ like that word. He doesn’t like to be called a hero, but he is.”

In writing the book, Trendos hoped to instill the importance of remembering the events of the Second World War.

“I’m not sure if we were in the same boat today that – I’m not sure our young people would be lining up to enlist,” she said. “I would like them to appreciate, fundamentally, the importance of service.”

As for Wallace, all he wants the younger generation to think about on Remembrance Day is how to “live an honourable life.”